It's the year 2000. The music industry has undergone a massive shift. Digital music files are becoming the defacto method of distribution. The MP3 player is the new "walkman." Both new and old companies seek to capitalize on the future of music listening. Many of those companies will either go bankrupt or drop the MP3 player product line.

But one of them would produce an MP3 player that would ultimately be responsible for massive advancements in not only music listening, but how we buy things, access information, and interact with one another.

When Apple launched its first-generation iPod in 2001, no one knew the impact that this device would have as the predecessor of the iPhone. The first iPod launched as "a thousand songs in your pocket," with 5GB of storage, a game-changing "click-wheel," and a sticker price of $399.

I bought one.

It was a fantastic piece of technology at the time. But, for a price tag of $399, the original iPod was useful to me for only about a year until the new generation was released.

When we make any decisions with our money, we always have a choice -- to buy or not to buy, this or that. Often we consider the cost of a buying decision in a one-dimensional manner: What is the cost of this purchase? However, all buying decisions are two-dimensional -- there's the cost of the purchase, and there's the foregone opportunity of doing something else with that money.

I'm sure I enjoyed that iPod, but what did I give up if instead of purchasing an iPod, I bought $399 of Apple stock?

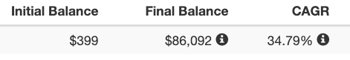

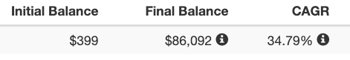

If I had the foresight to buy a tiny sliver of this Apple business instead of the widget they produced, that $399 would be over $86,000 today.

I'll give you a moment to catch your breath.

I don't know about you, but I

definitely would rather have $86,000 than an iPod for a year. Of course, we all know how difficult it is to pick these gangbuster stocks ahead of time. It's all a matter of luck, really. However, the point remains: There is a hidden cost to all of our financial decisions.

Economists call this Opportunity Cost: The loss of potential gain from other alternatives when one alternative is chosen. The Opportunity Cost of buying the iPod instead of Apple stock in 2001 is $85,601 ($86,000 minus $399).

So how can awareness of Opportunity Cost help you make better decisions today?

We have to buy things to live our lives. However, having an understanding of Opportunity Cost can help reframe certain purchasing decisions in light of your long-term financial goals.

For example, let's say you need a new car that you expect to drive over the next five years. You are waffling over whether to buy a $60,000 new car or a $30,000 used car. I'm not trying to tell you how expensive of a car to buy, or to shame anyone for how much money they spent on a car. We all have different goals, priorities, and budgets! Though adding the awareness of Opportunity Cost may help you rank your personal financial goals. So, let's do a little math.

If you purchased the used car, invested the $30,000 difference, and it earned 8% annually, your Opportunity Cost for buying the new car is $140,000 in year 20 and $652,000 in year 40.

Let me put that another way, choosing the used car may mean you get to retire one year earlier. Or allow you to pay for your grandchildren's college.

Having this awareness may help put your current financial decisions in context relative to your long-term goals.

Opportunity Cost is also a tremendous force when it comes to investment success. At my previous employer, we had a very successful client who made nearly $1,000,000 per year at the age of 40. He was pitched a private investment by some childhood friends who said they would

10X his money. The ask? $1,000,000.

Our conversation went like this:

CFP®: "This is a very risky investment. We don't think you should do it." Client: "I'm going to do it." CFP®: "There is a high probability that you'll lose all of your money." Client: "If I lose it all, I'll just have to work one extra year to make my $1,000,000 back." CFP®: "No, you may have to work an extra seven years." Client: "What!? How does that work?" CFP®: "$1,000,000 today, if invested prudently and earned 8% over the next 25 years, would be $7,000,000 at your retirement date. Your true loss is not $1,000,000. It's what that $1,000,000 might grow to if invested differently." Client: "Yeah, but if this investment works out, I'll have $10,000,000."

CFP®: **facepalm**

He made the investment. Not only did he lose all the money, but he also lost his childhood friendships.

Due to the nature of compounding returns, poor financial decisions can profound opportunity costs. A $10,000 mistake or missed opportunity does not cost $10,000. It costs $10,000 compounded throughout your lifetime, and perhaps your children's lifetimes (if you have them).

That car that costs $30,000 more than you need doesn't cost $30,000 more, it costs $30,000 compounded over your lifetime, and perhaps your children's lifetimes.

The potential gain of your alternative options is one of the most important considerations when making financial decisions. If you don't take it seriously, it could cost you.

I bought one.

I bought one. -1.png)