Private Equity typically refers to investment funds that are organized to invest directly in private companies; that is, companies not listed on a public stock exchange. During his failed 2012 presidential campaign, Mitt Romney's previous work at Bain Capital – one of the largest Private Equity players in the world and where Romney made his fortune – put a public spotlight on Private Equity.

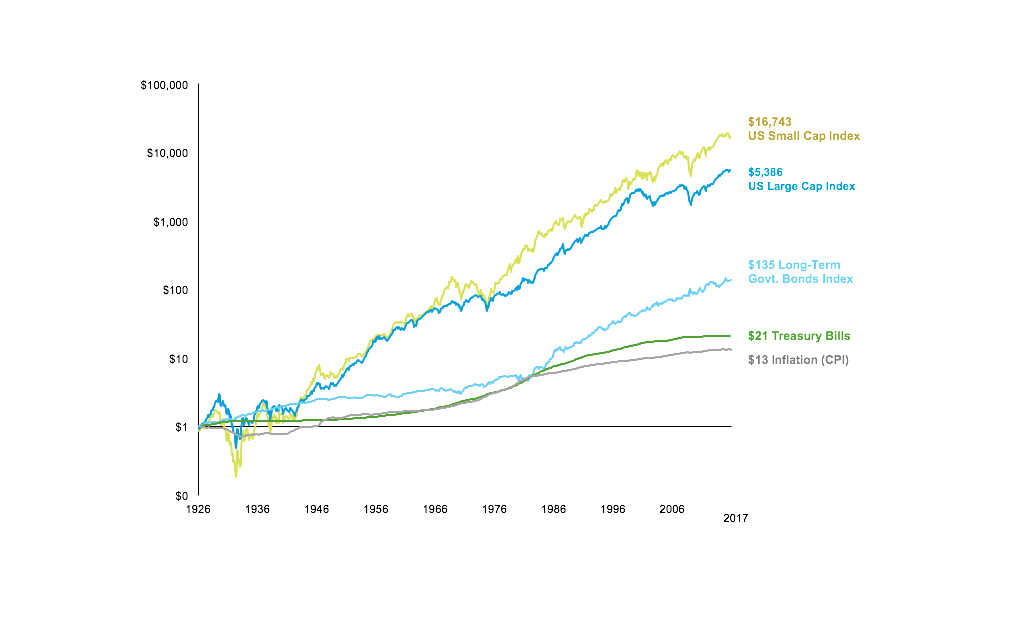

Private equity (PE) funds are primarily made up of large institutional investors, university endowments, and/or wealthy individuals. In recent years, a significant amount of capital has flowed into this space as investors seek a higher rate of return than what is offered in the public markets. By and large, it has been a smart move: the average PE investment has outperformed the broad public market since 1993.

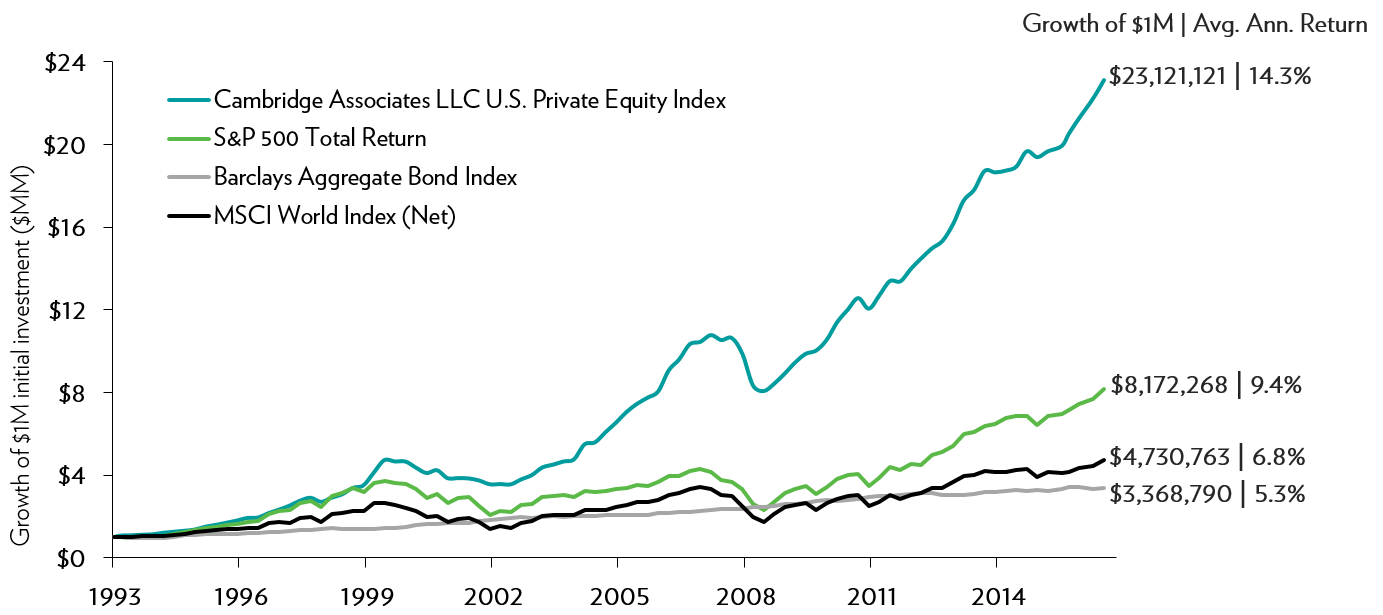

The chart pictured above was sent to me by a friend who runs a PE fund. I have no doubt that this chart has convinced a lot of people to invest their money with my friend's fund; in fact, I bet you're wondering whether you should follow suit right now. It’s tempting! But let's not get ahead of ourselves – first, we need to take a closer look at Private Equity.

Risk and return are two sides of the same coin that is investing. As investors, we can’t expect to receive any return on our money without bearing some amount of risk. As a general rule of thumb, as an investment's potential return increases, so does the risk. When you come across an investment that has outperformed the broad public markets, it can be really easy to focus only on the gaudy numbers. But your first thought shouldn't be "How soon can I invest everything I have into this?"; rather, it ought to be "What risks are associated with this asset that made the higher return possible?"

The most reliable and academically-proven way to evaluate the risk and return of a portfolio is the Fama/French Three-Factor Model. The gist of the Three-Factor Model is that stocks are riskier than bonds, small companies are riskier than large, and value companies are riskier than growth companies. The Three-Factor Model is said to explain 96% of all market returns; that is, we can look at the performance of a portfolio and attribute most of its return to some combination of those factors.

Since Stocks, Small Stocks, and Value Stocks are all riskier than their counterparts – Bonds, Large Companies and Growth Stocks, respectively – a portfolio that over-weights Small and Value Stocks should command a higher rate of return than a portfolio of Large and Growth Stocks. After all, you're taking on more risk, so the reward should be higher as well.

So, let's apply this to Private Equity. Using the Three-Factor Model as our guide, we can identify what additional risks there are to Private Equity investments. Identifying those risks will help explain Private Equity's historical outperformance of the broad public markets; more importantly, it will ultimately help you decide whether PE has a place in your portfolio.

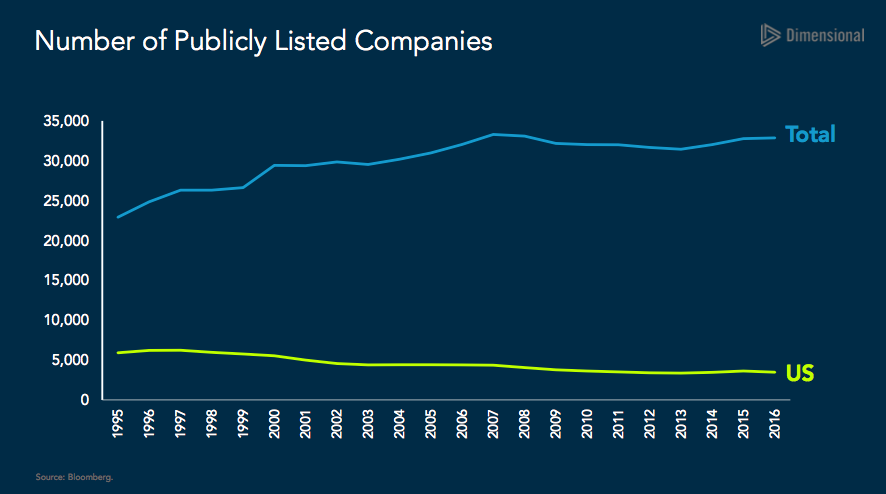

In the chart above, you’ll see that while the number of listed worldwide publicly-traded stocks have increased over the past 20 years, the number of publicly-listed U.S. stocks has shrunk. That doesn't mean that the number of U.S. companies has decreased, but that the number of companies deciding to go public has declined. And why is this important? Simple: the more private companies there are, the more opportunities for Private Equity investment.

Historically, small and growing companies that needed to raise capital to cover the cost of their rapid growth had one option: go public. But with the rise of PE funding, many small companies are opting to raise capital through PE investment rather than going through the trouble of becoming a public stock.

While there are many large private companies that would otherwise be in the S&P 500, a majority of private companies are small. According to the Three-Factor Model, small companies are riskier; as such, they command a higher expected return than large companies. In addition, Private Equity investors are typically looking to "flip" companies: buy floundering or cash-poor companies at low prices, then work to make these companies more profitable so they can be resold at a higher price. (Mitt Romney's old employer Bain Capital often used massive layoffs as a way to increase the profitability of the companies they purchased; this practice led some people to call Romney a "vulture capitalist.") Regardless of the methods used to increase profitability, flipping companies is a form of Value investing, which means that Private Equity is also heavily exposed to the Value factor.

Therefore, according to the Three Factor Model, PE is heavily weighted towards Stocks, Small Stocks, and Value Stocks – all risk factors that have the highest expected return within the model.

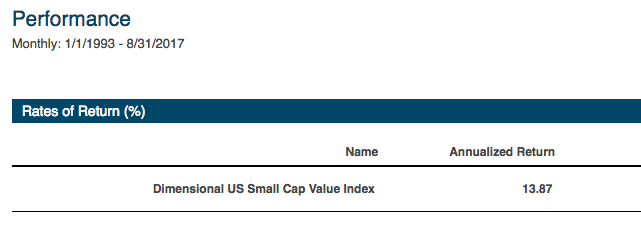

Now that we have identified Private Equity’s risk profile according to the Three Factor Model, let’s go back to 1993 (where the PE performance chart begins) and compare PE Index returns with the returns of PE’s publicly traded counterpart: the US Small Value company index.

As you can see, while the Cambridge US Private Equity Index compounded return for this period was 14.3% annualized, the Dimensional US Small Value Index returned 13.87%. Not far off! We just demonstrated that the Fama/French Three-Factor model was able to explain 97% of the Private Equity returns! But what about the 0.43% outperformance of PE over this time period? Are there other risks inherent in PE investments that don't exist with with public Small and Value companies? Let’s take a look.

As you can see, while the Cambridge US Private Equity Index compounded return for this period was 14.3% annualized, the Dimensional US Small Value Index returned 13.87%. Not far off! We just demonstrated that the Fama/French Three-Factor model was able to explain 97% of the Private Equity returns! But what about the 0.43% outperformance of PE over this time period? Are there other risks inherent in PE investments that don't exist with with public Small and Value companies? Let’s take a look.

Private Equity is notorious for their use of leverage in order to enhance returns; that is, they often use borrowed money to gain stakes in private companies. You don’t have to look further than the recent bankruptcy of Toys ‘R Us to see the potential risk of leverage employed by PE investment. Any time you use borrowed money, you increase the risk profile of the investment: If your investment goes belly-up, not only do you lose your investment, you still owe the bank.

Another risk associated with PE is a lack of liquidity. Since private companies are not publicly traded, it's not easy to find a buyer if you want to sell, which is why it’s not uncommon for a PE deal to lock up investors’ money for 5-10 years. When there is a lack of liquidity, investors expect a higher rate of return in order to compensate them for not having access to their money. That’s another risk that public Small Value companies avoid by being listed on a stock exchange that brings together buyers and sellers.

Unlike the Small and Value factors, there are no PE indices available for use by retail investors. Therefore, if you want the returns PE investments can offer, you have to take what's known as "manager risk" to get them. In a nutshell, manager risk is the risk that the given portfolio manager you select ends up being a chump. Manager risk is unique: it's one of the few risks that you can't avoid when investing in PE, but even though you have to take on that risk, doing so doesn't historically yield a higher rate of return for investors. As the saying goes, hindsight is 20/20: it’s easy to see which managers have performed best in the past, but identifying future top performers is more difficult – and more of a gamble.

Additionally, since no PE index exists, typical PE funds charge a 2% management fee and take an additional 20% of profits. That means that if you invest with an average PE manager, your after-cost return would be well below the return of a passive Small Value manager like Dimensional Fund Advisors who only charge .5%.

Private Equity investments look like a no-brainer on paper, but once you peel back the layers, there are a lot of reasons to think twice about them. No matter what asset you're considering investing in, first ask yourself one question: is this asset worth investing on a risk-adjusted, after-cost basis?

By comparing PE to Small Value in terms of risk profile of the companies typically invested in, the leverage, liquidity, and manager risks, and the expected costs associated with PE vs. Small Value, the answer is clear: a passive Small & Value fund is the better – and safer – bet.

This material is intended for educational purposes only. You should always consult a financial, tax, or legal professional familiar with your unique circumstances before making any financial decisions. Nothing contained in the material constitutes a recommendation for purchase or sale of any security, investment advisory services or tax advice. The information and opinions expressed in the linked articles are from third parties, and while they are deemed reliable, we cannot guarantee their accuracy.