April 17th, 2018

It was just another ordinary travel day for Jennifer Riordan.

For the 43-year-old bank executive and mother of two, April 17, 2018 was a travel day just like any other. Just as she had countless times before, Jennifer kissed her kids goodbye and headed to the airport, then boarded Southwest flight 1380 bound for Philadelphia. She settled comfortably into seat 14A; a window seat. The days of pre-flight anxiety were a thing of the past for Jennifer – her travel requirements had increased as her career advanced, and by this point in her career she was an experienced business traveler. She had taken hundreds of flights in her life, all without incident. But that day was different. On April 17th, 2018, Jennifer Riordan boarded her plane, and she never came home.

The takeoff was uneventful, and soon the plane had reached its cruising altitude. Moments after the flight attendants began taking drink orders, there was a loud pop and the oxygen masks deployed in the cabin. One of the engines on the plane had disintegrated, sending shrapnel in all directions. A piece of the engine slammed into the plane, shattering one of the 10" x 14" cabin windows: the window in row 14. The rapid depressurization sucked Jennifer halfway out of the window. She died instantly.

It is not uncommon for a plane malfunction to end in tragedy. In this instance, however, it is more surprising that a catastrophe of this magnitude only claimed a single life. It was a freak accident that is unlikely to occur again – Jennifer Riordan just happened to be in the wrong seat at the wrong time.

Choosing Your Own Seat

If you've ever flown Southwest, you know the airline has a unique boarding process: they don't assign seats. Instead, you receive a number that determines when you can board; once you're on the plane, you can take any open seat you'd like. Southwest's boarding process, coupled with the knowledge of Jennifer Riordan's freak accident, makes for an interesting psychological experiment.

Just one day after the accident, my high school best friend Justin boarded a Southwest flight for his own business travel. He checked in late, which meant he was assigned a high boarding number and, therefore, would be one of the last people to board the plane. Under normal circumstances, all the window and aisle seats would have been taken by the time Justin boarded the plane. But this time was different.

Just one day after the accident, my high school best friend Justin boarded a Southwest flight for his own business travel. He checked in late, which meant he was assigned a high boarding number and, therefore, would be one of the last people to board the plane. Under normal circumstances, all the window and aisle seats would have been taken by the time Justin boarded the plane. But this time was different.

As Justin boarded the plane, he saw the usual open middle seats – nobody's first choice for a comfortable flight – yet there was also a single, unoccupied window seat: 14A.

Like everyone who boarded before him, Justin had a decision to make. He knew that 14A was Jennifer Riordan's seat, and with the accident fresh in his mind, he weighed whether to tempt fate by taking that seat. But Justin's rational mind won the battle: he determined that the accident that killed Jennifer Riordan was a freak occurrence, and that the odds of the same thing happening on a different flight were infinitesimal. After his initial hesitation, he took the row 14 window seat and, in true Justin fashion, made a joke about it to the flight attendant. Everyone laughed – he was acknowledging what they all felt but weren't comfortable saying out loud.

Recency Bias

Let's say 200 people boarded that plane before Justin. Why did each one of those passengers refuse to take that window seat? And why would so many passengers prefer to cram themselves in the middle seat – effectively guaranteeing they'd have an unpleasant flight – than sit in the available 14A?

Because humans aren't always very rational. It's called the "recency bias": our brains give more weight to recent events relative to older ones. The odds that a Southwest plane would have a repeat of the accident that claimed Jennifer Riordan's life – especially the very next day – are so minuscule that they're impossible to calculate. Yet every passenger except Justin fell prey to recency bias: they assumed that what had happened the day before was likely to happen again, even though the initial accident was a statistical outlier to begin with.

Our minds have a stronger emotional connection to events that occurred recently. Can you imagine hearing about the flight 1380 accident the day before you were set to board a Southwest flight? No matter how statistically unlikely that accident was, in the minds of those passengers, they all saw themselves in Jennifer Riordan: just another passenger on a routine Southwest flight.

Prospect Theory

We also tend to make decisions based on the potential impact of losses and gains where an outcome is uncertain. For the Southwest passengers, even though the chance of that accident happening again was so small, the potential loss was huge: their lives. We have an innate aversion to loss because the pain of loss has a greater impact on us than the pleasure of gain.

The passengers on Justin's flight ran a quick (albeit irrational) calculation in their heads as they approached row 14. It went something like this: The risk of taking that seat is potential death, and the cost of protection is the discomfort of sitting in a middle seat -- I'll absorb the minor cost to protect against the potential loss.

Investing and Yesterday's Headlines

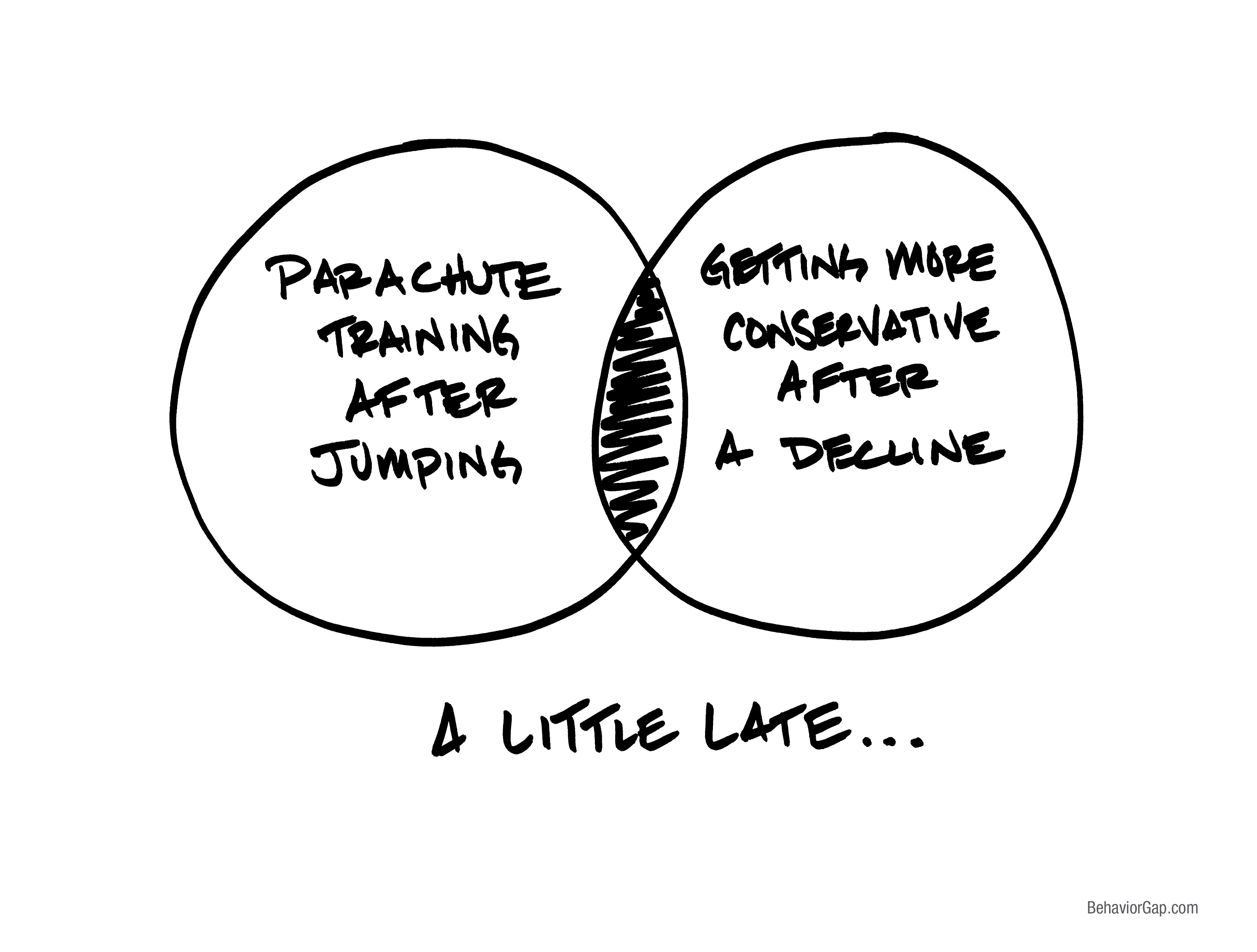

This irrational calculation happens in our heads all the time, especially when it comes to investing. Whenever the stock market experiences a significant decline, many people are traumatized by the loss, making them more reluctant to invest in the future. To some, the markets are a frightening place where their uncle lost all of his money.

When we see our money going down in the stock market, we biologically interpret it as a threat. We tend to avoid threats that are felt most recent -- whether it's a seat on a Southwest Airlines flight or an investment that has declined in value.

This presents an opportunity to those who don't mind sitting in the proverbial seat 14A. Those who can identify and avoid that irrational behavior are able to take advantage of opportunities that others might avoid. And you can gain while others are focused on avoiding loss; after all, Justin was able to enjoy the comfort and view of a window seat instead of being stuck in the middle.

Yesterday's headlines often concern the threats that were unexpected and are the least likely to happen again – that's why the car crash a few towns over from you didn't make the front page of the Washington Post. Investing is no different. When irrational investors flee stocks because of a recent scary headline, there is opportunity for you there. The next time that happens, don't be afraid to take a seat.

This material is intended for educational purposes only. You should always consult a financial, tax, or legal professional familiar with your unique circumstances before making any financial decisions. Nothing contained in the material constitutes a recommendation for purchase or sale of any security, investment advisory services or tax advice. The information and opinions expressed in the linked articles are from third parties, and while they are deemed reliable, we cannot guarantee their accuracy.