-2.png)

Quote to Ponder

“At 10 times revenues, to give you a 10-year payback, I have to pay you 100% of revenues for 10 straight years in dividends. That assumes I can get that by my shareholders. That assumes I have zero cost of goods sold, which is very hard for a computer company. That assumes zero expenses, which is really hard with 39,000 employees. That assumes I pay no taxes, which is very hard. And that assumes you pay no taxes on your dividends, which is kind of illegal. And that assumes with zero R&D for the next 10 years, I can maintain the current revenue run rate. Now, having done that, would any of you like to buy my stock at $64? Do you realize how ridiculous those basic assumptions are? You don’t need any transparency. You don’t need any footnotes. What were you thinking?”

—Scott McNealy, CEO of Sun Microsystems

In 2004, I graduated college and received my first real money—a generous $10,000 gift from my grandpa. I took it to a financial advisor (who is still a mentor of mine). Instead of giving me a list of stocks, he decided to teach me something and challenged me to pick my own, saying, “Let’s see what you’ve got.”

Armed with my meager research skills, I set out to find investments that would yield quick, but consistent returns. I felt I knew a bit about market history (the tech bubble had recently burst—steer clear of tech) and had a geopolitical outlook (the USA’s best days might be behind it).

Armed with the above vague principles and a few primitive screens from Schwab, I set out to make my fortune and impress my mentor. I looked for funds that fit my story. I was smart enough not to look solely at 1-year performance (brilliant!), so I focused on the long term, which to my 22-year-old self meant…. five years.

From what I can remember, I pulled up the top-performing funds and diversified among them, or so I thought. In reality, since I didn’t know what I was doing, I ended up putting my entire portfolio into Emerging Markets and paying a 5% commission to do it. Their stellar performance drove this: up 21%/year over the past five years, 37%/year over the past three, and 41% over the past 12 months. It seemed like a sure bet.

Of course, it didn’t last. Emerging Markets (MSCI Emerging Markets Index June 2006-June 2016) floundered and averaged a paltry 3.4% over the next 10 years (lucky I learned to adopt a more prudent strategy long before June of 2016).

Today's Trap

If a young graduate were investing today, they might fall into the same trap, chasing the top-performing funds of the past five years. US Growth stocks, averaging 18%/year over the last five years (and 15%/year over the last 10), would likely be the target (Fama/French US Growth Index through 5/31/2024).

Many important asset classes would be ignored for “underperforming.” Today’s young investor might avoid International Stocks, which have averaged only 3% per year over the last three years, or Small Value Stocks, which have averaged just 4%. Emerging Markets, losing 6%/year for the last three years, would be completely off the table.

However, just as we shouldn’t put all our money into tech stocks or emerging markets, we shouldn’t put all our money into US or growth stocks either.

Tech Bubble-like Valuations?

Consider the above Sun Microsystems quote. Following the tech bubble (and the price-to-sales ratio of 10), Sun Microsystems dropped from a valuation of $200 billion to $3 billion before ultimately being acquired by Oracle. It is very difficult to justify a price-to-sales ratio of 10 or above.

Today, when you buy the S&P 500 (the largest 500 companies in the USA), about 40% of your money goes into just 10 stocks. Of these 10 stocks, 7 of them have a price-to-sales ratio of 10 or greater (as listed below).

- Microsoft: 15

- Apple: 10

- NVIDIA: 42

- Meta: 10

- Broadcom: 18

- Eli Lilly: 23

- Tesla: 10

The Underperformers

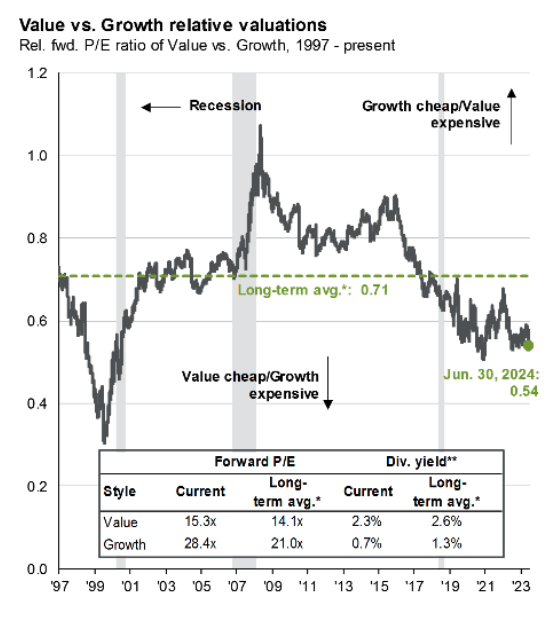

What about those “underperforming” asset classes? What could be attractive about them? According to JP Morgan’s excellent Guide to the Markets, Value hasn’t been this cheap relative to growth stocks since the tech bubble.

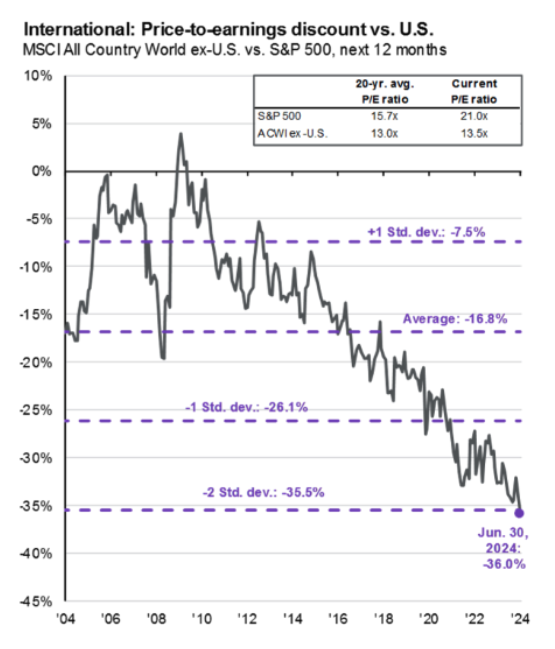

Furthermore, international stocks haven’t been so cheap compared to US stocks in decades.

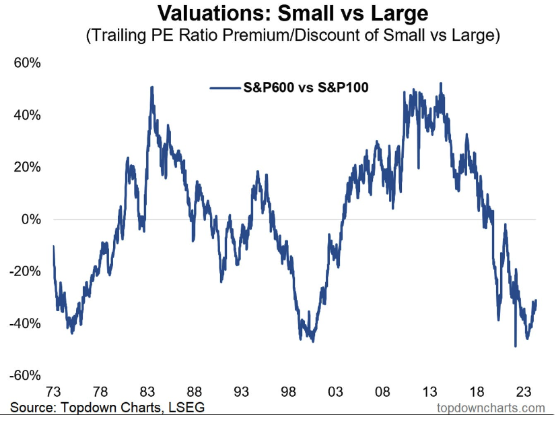

Last of all, small stocks are historically cheap relative to large stocks as well.

Young Bjorn would have been wise to remember Warren Buffett’s adage: “Price is what you pay, value is what you get.” He would have done well to understand recency bias—the tendency to favor recent events over historic ones. He would have realized that a long-term perspective is much longer than five years—and that the only way to invest is with a truly long-term outlook. Most importantly, he would have learned that in investing, as in life, humility is a virtue - so don’t put all your eggs in one basket.

More reading:

Can the US Continue to Outperform

Large-Growth Stocks are Overvalued. Small-Value Stocks are Undervalued.

This material is intended for educational purposes only. You should always consult a financial, tax, or legal professional familiar with your unique circumstances before making any financial decisions. Nothing contained in the material constitutes a recommendation for purchase or sale of any security, investment advisory services or tax advice. The information and opinions expressed in the linked articles are from third parties, and while they are deemed reliable, we cannot guarantee their accuracy.